NucliaDB Index: Powering Fast, Smart and Scalable RAG

Previously published on Nuclia.com. Nuclia is now Progress Agentic RAG.

NucliaDB is a core component of the Nuclia platform, designed to store all processed data uploaded by customers and to coordinate Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) queries efficiently across that data. One of the main components of NucliaDB and the subject of today’s article is the indexing system, which indexes all text extracted from customer documents, as well as the inferred entities and semantic vectors. This powers the fast search capabilities that are the building blocks of RAG features.

A Multimodal Index

From the beginning, we knew that a single kind of index would not be enough for our plans, so we architected our index server to support different kinds of indexes for different purposes. Now, we store four different indexes for each knowledge box:

- A document index. This is used to quickly list and find documents based on their properties (user-specified labels, file type, upload date, etc.). This supports a good part of the filtering features available in Nuclia.

- A keyword index, used for finding text blocks (paragraphs) that match given keywords and ranking based on Best Match 25 (BM25) scores.

- A vectors index to support semantic searches on text blocks, implementing different semantic models and vector types.

- A knowledge graph index to power the navigation of our automatically generated knowledge graphs.

A key capability of Nuclia’s index server is to perform hybrid search, that is, the ability to combine information from all the indexes listed above to find the best results. As mentioned above, one way this is useful is by being able to filter documents based on multiple indexes, for example, "Give me all the documents of type video, uploaded in 2024, that contain the word search".

For this example, this is achieved by first filtering in the document index for the file type and upload date, and building a sparse vector of the document IDs that pass the filter (or, if there are many matches, we can build the vector of documents that fail the filter). This is followed by a search on the keyword and semantic indexes using the previous vector of documents as a filter and looking for the keyword, returning sorted results.

To support this capability, all indexes share the same document IDs, and each of them implements filtering based on the set of document IDs (using the techniques best suited for that index). Additionally, the index server has a query planner that’s able to parse a RAG query into a set of queries specific to each index, and the operations needed to combine the filters and results.

As a final step before returning the results to the user, we rank them in order of relevance. This is not trivial, as they may come from matches in different indexes when using hybrid search to find results in both the keyword and vector indexes, with different scoring systems. There are different algorithms to perform rank fusion (this operation) and NucliaDB supports configuring the one to use at query time to the most appropriate for each use case.

Finally, the results can optionally be re-ranked before returning them to the user. This technique uses a language model to reorder the results in order of relevance, which is especially useful when presenting the list of results directly to the user, to help the most relevant results show up first.

A Fast Index

In the context of RAG, retrieval speed is a key metric. Write speed is also important but not as critical, since processing and indexing is done as a batch job in the background (and processing is slower than indexing anyway). For this reason, we designed our indexes optimizing for retrieval speed first, and indexing speed second.

For the keyword search, we used Tantivy, an open-source search engine that fulfills our needs, with some customization of our own to better support filtering across different indexes and fuzzy search.

For the semantic index we implemented our own system from scratch, because we were among the first to work on vector indexes and there were no implementations suited for our needs at the time (among others: supporting multiple types of vectors, quantization, scalability). Even today, with many solutions in the space, our solution is very performant and scalable, and we see no need to replace it.

Fast Reads

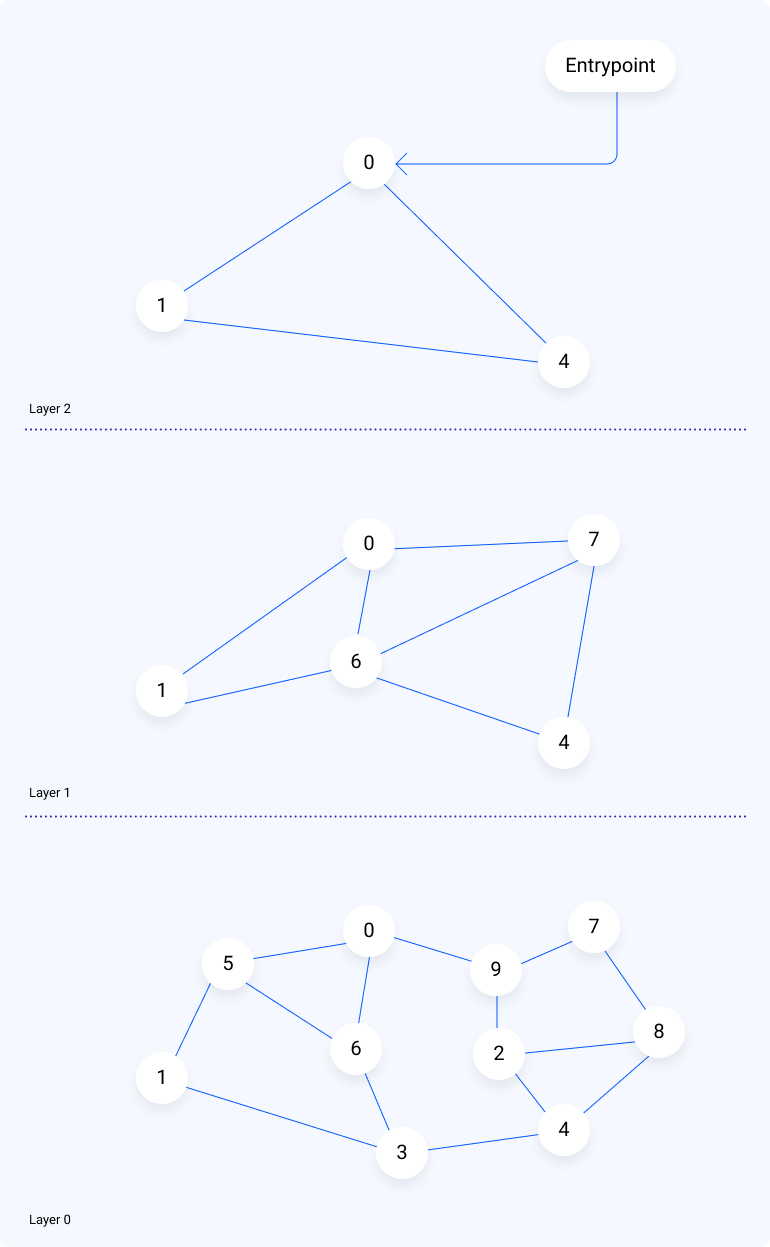

With this in mind, we chose to build our vectors index using the Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) algorithm, which provides great results quickly at the cost of insertion speed. This algorithm builds several layers of graphs of related vectors, where each layer is a subset of the lower layer. To search, we find the closest vector to our query in each layer before going down to the next. This has the effect of quickly closing in on the area of our query, which results in much fewer vector comparisons (which are slow when vectors are large).

To make reads fast, we try to keep as much of the index as possible in memory, especially the graphs in the top layers as they are small (fit into memory) and used by all queries. To account for this, the vectors index is structured so the files in-disk are ordered by layers. The files are then memory-mapped into RAM, and we send hints to the operating system to prioritize keeping the top layers in memory for quick access. As one index of the graphs is traversed, we pre-fetch the corresponding nodes in the lower layers to speed up the query.

Fast Writes

As mentioned above, one downside of HNSW is that the insertions are quite costly, since they involve searching the entire graph to find the best insertion spot for the new vector. Doing so in a big graph is a costly operation that can easily take a minute when inserting a large batch of vectors from a single large document.

To make the indexing latency as small as possible, we use a different strategy. When inserting a batch of vectors, we create a new "segment" (a separate HNSW graph) and insert the entire batch. This is very fast and allows us to return search results from newly indexed documents just a second after they're indexed.

However, this speed comes with a cost in the retrieval phase, because now the search has to look for documents in each of the segments and merge the results, which is slower and can be inaccurate. Ideally, we want a single segment.

A background job merges all the segments of a knowledge box into one. This can take a few minutes for large graphs, but it improves retrieval speed and accuracy. We use several tricks to keep this responsive, such as reusing parts of the segments when merging into a single one (to avoid recomputing all graph edges from scratch), but it’s still an expensive operation.

Something similar happens for deletes: a delete operation just marks the document as deleted in the index so it stops appearing in results immediately, while the background job actually deletes the node from the graph at a later point in time.

This solution enables us to have the best of both worlds: low latency from document being processed/deleted to it showing up in searches and a guarantee that the graph will be optimized eventually to get the best possible performance.

While our index is feature-packed and we designed it to be fast, there is another key point when operating a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) product: it needs to be scalable.

2: Scaling the RAG Index

Clustering Data

The main idea we use for scaling is to split data into smaller chunks (shards) that contain only a subset of the resources of a knowledge box. The idea is that we can distribute each shard to a different machine so that multiple machines can intervene in a search request to minimize latency. Each search request will need to search in all shards, then merge the results into a single response.

These shards are created by assigning each resource to a shard and saving this information into a metadata store. All further modifications and/or deletions for that resource are sent to that specific shard. Since these operations are uncommon in RAG use cases, we can get away with the performance hit of querying the metadata store. We also gain more control over how resources are assigned to shards to optimize the amount and kind of resources stored in each one.

The time for a search request can be expressed as the time to search in the slowest shard plus the time needed to merge the results from each shard. Bigger shards make the first part of the equation slow, while smaller shards make the merging part slow, so a sweet point needs to be found. In our case, this currently turns out to be around 2M paragraphs per shard for most Knowledge Boxes, although it changes frequently as we make changes to our search algorithms.

Our first approach to store and query all of this data was to have data nodes that each store a set of shards and handle all the operations for them,including insertions, deletions and searches. Shards are distributed in such a way that each Knowledge Box ends up with data distributed equally across all nodes, and searches can benefit from the scale of using multiple search nodes.

Finally, to scale searches, we implemented a read-replica system for index nodes. Each storage node can have as many replicas as needed to serve all the search requests. Replication uses a relatively simple leader-follower approach that consists of applying a stream of all disk operations from the leader node in each follower.

The Limits of the System

There are multiple problems with this approach that limit scalability:

- It’s hard to scale up and down the number of nodes because they store the data, so scaling means moving data from node to node in order to keep the distribution even.

- The write operations can affect the performance of concurrent searches. In a RAG use case where writes are batch operations and searches are interactive, this significantly worsens user experience.

- All operations for a shard always hit the same node, which can become a bottleneck. This is especially problematic when serving big spikes of writes for a subset of shards, which is a common pattern with RAG use cases when the user's dataset is first uploaded and processed.

A New Architecture

When presented with these challenges, we started looking at ways to solve this. In particular we wanted to:

- Be able to easily scale writes under spiky loads. This meant separating the CPU-intensive part of the indexing from the storage itself.

- Be able to scale the number of search nodes independently of the write/storage nodes. We already have this with node replication, but we wanted additional flexibility to add/remove search nodes and increase distribution of searches against hot shards.

- Searches should be unaffected by intense write spikes. A delay from indexing a resource to it appearing on searches is OK; a slow search is not.

A popular choice to achieve this is to completely separate computing from storage. This results stateless nodes for writes/searches, and all the data is stored in a separate storage cluster, usually object store (S3/GCS) when running on the cloud.

Although this works well for text indexes (and there are multiple products implementing this idea), it is very difficult to make this work with vector indexes in general, and HNSW in particular. The problem is that during a search, you end up computing the similarity of the query vector against many vectors in the index (on the order of 1,000).

Downloading a lot of relatively big vectors for each search is slow (even considering caching) and results in high latencies for searches plus an exaggerated cold-start problem. In fact, we already suffer from the cold-start problem when working with a dataset in local SSD storage, so trying to do this over a network would be inadmissible.

In the end, the best we can do is have the search nodes download the shards it needs upon startup and continually sync them. In this case, search will continue working similarly to how it worked with replication before (syncing data and working with it locally), but with added flexibility to distribute subsets of shards to each search node.

Writers Without Storage

In this new design, writers are much simpler. They take indexing requests from a work queue, create a new segment for the index with the corresponding data, upload it to the shared object storage and register the new segment in a metadata database.

As before, we need to periodically merge those segments into bigger ones to maintain good performance in our indexes. For that, we use a scheduler that continually scans the metadata database mentioned before to look for shards with too many segments and queue a job to merge them. A worker will then pick up that work, download the segments, merge them, upload them again and register the change in the metadata database.

This makes writes very easy to scale. The number of workers can scale based on the number of messages pending on the queue to scale up and down with demand. Since the workers do not have state, they are very quick to start up and shut down, allowing us to follow demand very closely.

One difficulty that this change entails is that workers may process indexing requests at different rates and insert segments into the index in a different order. This is only a problem when dealing with deletions/updates for the same resource: we want the order of the operations in the index to reflect what the user intended and index the latest version of a resource. To help with this, we track the order of operations (a sequence number) throughout the system, order segments using it, and only apply merges and deletions once we are sure we have received all messages that may affect such operation (we have received all sequence numbers prior to the time of the operation).

Searchers and Shard Replication

As mentioned above, each searcher node will need to replicate a subset of shards locally in order to serve them. Right now, the distribution of shards to nodes is done using consistent hashing , which allows us to scale the number of search nodes while keeping the size of the dataset in each node constant. At the same time, it minimizes the amount of balancing when adding/removing nodes.

Aside from the initial download, each searcher node subscribes to change notifications for the shards to which it is assigned. Upon receipt of a notification, it will use metadata to calculate a difference between the data it has stored locally and the current version of the data, and will download from object store the minimal amount of data it needs to update to the latest version.

The searcher node also keeps a cache with preloaded index data for the most recently used shards. After the synchronization is done, it will also reload this cache with the new data. We reload and swap (instead of just invalidating) the data to avoid the next query for that shard having higher latency (it would have to reload the data structures), which is undesirable for a shard we know is in use.

When compared to other solutions that decouple search computing and storage, this can be seen as preloading the local cache with all the data that it might possibly use. This reduces the latency significantly (since a search will never have to download data from the network) but it’s more wasteful since it uses a lot of disk space caching indexes that might never be used. As searches on the vector index scan a significant part of it on each query, and they are especially slow to download due to the size of the vectors, we think this is the only way to maintain the low response times expected from an interactive application.

Performance Validation

To validate the scalability claims of the new design, we did some quick benchmarking during the development cycle. This is not a comprehensive set of tests (although we are working on that) but offers some reassurance that we didn’t miss anything with the new design.

We worked with a dataset of 100k documents with 1k vectors each (for a total of 100M vectors of 1536 dimensions) and tested insertion, merging and query speeds as we increased the number of machines allocated to this job.

Indexing

For indexing, we tested with a variable number of indexers. These workers were stateless and easy to scale up/down, so we were not afraid of using many tiny ones for this task. In particular, we allocateed 1 CPU and 512MB of RAM per indexer in this test.

We can increase the number of workers to work as fast as we want to, until we hit the time taken to index a single batch, which, in Nuclia, is variable depending on the input documents and the processing step. In practice, indexing will not be the bottleneck and would be limited by the previous processing step. The scaling is approximately linear (twice the workers, half the time) as we expected.

Merging

After this point, the documents were ready to be searched, but the search would be slow because we had created many small indexes. As soon as we started processing some documents, the merge workers started merging into bigger and bigger indexes. This is an iterative process where each vector is merged multiple times into bigger and bigger indexes. It would be faster to do a single merge into the final index, but doing it this way allows for the user to perceive improvement in search times much faster.

We tried merging the previous dataset with a different number of workers (each 1 CPU core and 2GB of RAM) and measured the time until the index was completely merged.

Similarly to the indexers, we can scale linearly with the number of workers, although the time to merge is much longer than the time to index. Still, with enough workers we can completely ingest and optimize the index of 100M vectors in ~20 minutes. This is a consequence of a tuneable parameter of the system (the maximum segment size, set to 200k vectors in this test). Bigger graphs will take longer to generate (increase total merge time) but help search performance.

Search

After completely indexing and merging the dataset, we launched a series of searches against a varying number of search nodes (8CPU cores, 32GB of RAM), with the dataset segments equally distributed amongst all of them. We measured recall (0.924 across all tests), queries per second and the 99-percentile latency:

We saw approximately linear scaling in the queries per second. We expected to see better than linear in this particular example, because search benefits greatly from large amounts of RAM to cache the index and more RAM is available with more nodes. It seems we are more limited by CPU than RAM in this case.

On the query latency, we also saw good scaling although not linear (9.7x speedup with 16 nodes vs. a single node). This was expected, because although the operations in each node were faster, there was network latency and time spent merging the results to consider.

Conclusions and the Future

Changing from a fixed allocation of shards to storage nodes to a shared storage layer and dynamic allocations of shards to searches was significant. We think it was worth it since it has made the index faster (specially serving write spikes) and easier to scale, and the platform is more reliable and easier to maintain.

We expect further work to keep improving on this. In particular, we want to work on distributing shards to nodes so we can specifically distribute the most active shards across more nodes than other shards that are seldom used.

To see Nuclia in action, check out our demos or get started with a free trial.