The Slowing AI Narrative: A Dangerous Argument for Global Competitiveness?

When caution becomes a cage for the builders.

I still have the first API key I ever generated. It’s saved in that same old notebook where I, like many of you, scribbled down grand ideas after a lecture. Back then, the promise felt like raw material in our hands. We weren’t just learning syntax‚—we were being handed the tools to shape what came next. The dominant feeling wasn’t fear. It was agency.

Today, that agency is under siege. Not by a lack of tools, but by a growing chorus that questions our right to use them. The loudest debates in our feeds are no longer about how to architect a resilient system or fine-tune a model, but about whether the project itself is too dangerous to continue. The narrative has pivoted from “build” to “slow down.” From empowerment to apprehension.

And that’s what keeps me up at night. Not the necessary discussions about security or ethics, we should be having those at full volume. It’s the creeping assumption that the safest path is the one of least momentum. Or that the ultimate act of responsibility is to stop building.

But I’ve been in the trenches. I’ve seen what happens when AI is deployed without a human-in-the-loop. I know the risks are real. And that’s precisely why I believe this new “slow down” narrative isn’t prudent—it’s a profound strategic error. It mistakes hesitation for wisdom, and in doing so, it doesn’t mitigate risk. It simply transfers that risk, along with the future itself, to those who never asked for permission.

If it’s your job is to ship code, integrate systems or solve problems, this isn’t an abstract debate. It’s a directive that directly impacts your work, your tools and your potential. This article is about why that directive is flawed, and what we, as a community of builders, should champion instead.

Let me be clear: the fear driving this narrative isn’t coming from nowhere. I’ve had to roll back a model in production. I’ve seen a hallucinating LLM generate valid-looking but fatally flawed code. This anxiety isn’t abstract panic—it’s a direct response to the messy realities of pushing this technology to its limits. When deployments can impact financial transactions or automated decisions, wanting a kill switch isn’t paranoia. It’s professional diligence.

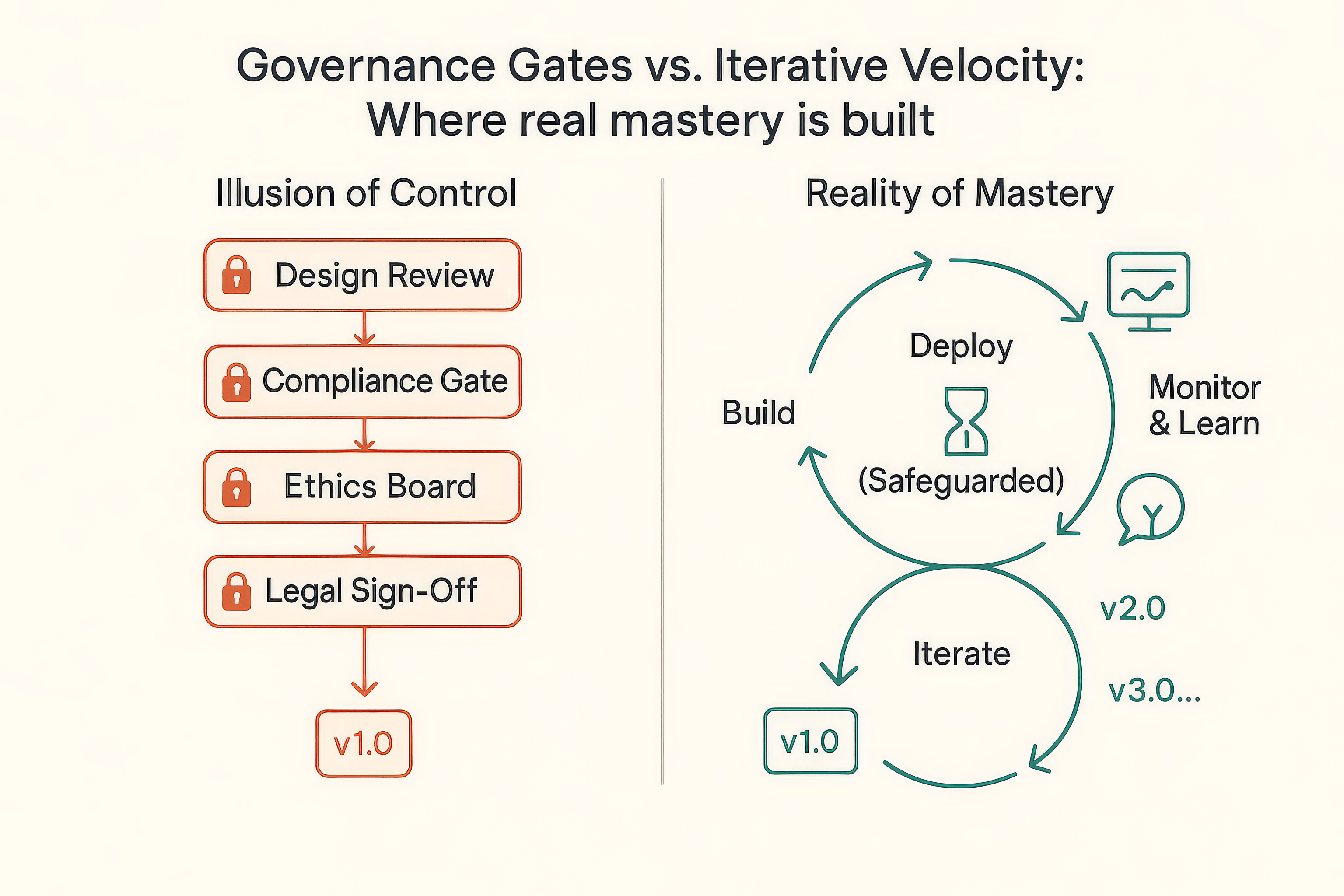

As a technical community, we’re making a critical category error by conflating risk management with risk avoidance. We’re building longer and longer approval chains, more complex ethical review boards and stricter compliance gates, believing that if we just add enough friction, the risk disappears. This isn’t engineering. It’s superstition. It’s like trying to prevent bugs by refusing to compile your code.

Meanwhile, the actual work of understanding and taming these systems isn’t happening in our stalled committees. It’s advancing in environments where “move fast and break things” isn’t a discarded motto—it’s the operating manual. While our CI/CD pipelines are choked with new governance steps, theirs are running. They are the ones encountering the edge cases, patching the vulnerabilities and, critically, learning the empirical truths about what makes these systems robust or fragile in the wild.

Fear directs all our attention to the single, catastrophic if statement: what if it goes wrong? This makes us excellent at writing pre-mortems. But it blinds us to the slower, more insidious bug that’s already in production: what if going slow is the very thing that breaks our ability to lead? The product manager waiting for a regulatory greenlight, the startup that can’t access cloud credits for “high-risk” AI research, the open-source project that gets forked and stripped of its safeguards abroad…their reality is a roadmap being rewritten by indecision. By prioritizing the elimination of all technical risk, we are systemically introducing a massive strategic vulnerability.

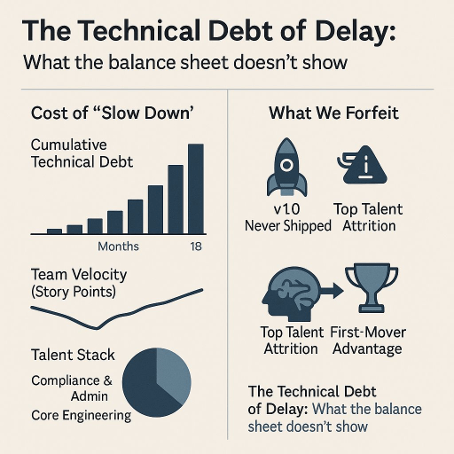

In our world, progress is measured in shipped features, resolved tickets and improved latency. So let’s measure the cost of this prudent delay in the currency we understand: lost iterations.

Picture a senior engineer on a healthcare tech team. She’s architected a novel pipeline that uses a fine-tuned model to flag anomalies in medical imaging data—anomalies human radiologists often miss in early stages. The prototype works and the potential is staggering. But the legal and compliance review for a full-scale clinical trial is estimated at 18 months, a timeline driven more by liability fears than scientific rigor. Every sprint she spends in this holding pattern isn’t just lost time; it’s a version of the product that will never be tested, a cycle of feedback that will never happen and a dataset of real-world performance that will never be collected. This is technical debt of the highest order, incurred before a single line of production code is written.

Now, shift your focus from the product to the pipeline, the talent pipeline. I talked to junior developers from the University of Kinshasa who are brilliant at PyTorch but disillusioned by the landscape. They graduated wanting to build systems that matter. Instead, they’re handed a rulebook thicker than the framework documentation, tasked more with navigating audit trails than training loops. The most creative minds are voting with their feet, moving into domains where the rate of iteration and, therefore, learning is still high. We aren’t just slowing down projects. We’re downgrading the entire talent stack to work on our most critical problems. A culture that prioritizes perfect compliance over learned resilience doesn’t attract pioneers. It attracts administrators.

This is the real balance sheet of the “slow down” mandate.

On one side: a potential, mitigable bug or oversight. On the other side, guaranteed and compounding costs, architectural stagnation, talent attrition and the existential threat of a competitor’s 18th iteration facing your cautious, never-deployed version 1.0. It frames the act of building as the primary danger. But in our line of work, the greater danger has always been not shipping. Not learning. Not adapting. Choosing the known failure of a stagnant codebase over the manageable, iterative risks of a live one.

There’s a dangerous illusion in our boardrooms and stand-ups: that adding more governance gates to our development sprints means we’re governing the technology itself.

We think we’re implementing a cautious, controlled rollout. In reality, we’re voluntarily exiting the arena where the real-world stress tests happen—the only place where true robustness is forged.

Reframe the competition. It’s not about who has the biggest model. It’s about which ecosystem achieves mastery through volume and velocity of real-world iteration. The nation, company or developer community that gets its v1.0 into the hands of users (with safeguards) and iterates to v10.0 while others are still in design review, won’t just have a better product. It will have something far more valuable: deep, empirical, un-shareable knowledge. It will have encountered and solved the weird edge cases, the unexpected failure modes and the scaling headaches. It will have written the linters, built the monitoring tools and defined the MLOps best practices that everyone else will have to adopt. In short, it will own the stack. Not just the model but the entire operational reality around it.

Look at the history we’ve lived through. The early, open protocols of the internet (TCP/IP, HTTP) created a global playing field defined by certain values of interoperability and decentralization. Contrast that with the rise of tightly controlled, walled-garden platforms that followed. The initial architectural decisions set a trajectory for decades. The AI infrastructure layer being built right now, the tools for evaluation, deployment and governance, is our generation’s TCP/IP. Will it be open, auditable and designed for human oversight? Or will it be proprietary, opaque and optimized purely for control?

By prioritizing risk-averse, pre-launch perfection, we aren’t avoiding a future shaped by AI. We’re blindly choosing which architects will design that future. We are conceding the foundational work, the hard engineering of making AI work reliably at scale, to those who view our ethical guardrails as inefficiencies to be bypassed. Our hesitation isn’t cautious governance. It’s the most consequential technical debt we will ever incur, a debt that will be paid in the currency of permanent dependence on foreign toolchains and standards.

So what’s the alternative for those of us whose job is to ship? It can’t be the reckless, untested deployment of yesteryear. That’s just technical debt disguised as velocity. But it also can’t be the innovation-crushing paralysis we’re veering into. We need a technical and cultural framework that allows for speed and safety. Not as a compromise, but as a synergistic system.

I call it the Builder’s Safeguard. It’s the principle that robustness is a feature, and it must be engineered in parallel with capability.

This isn’t a philosophical stance. It’s an architectural one. It means making three foundational shifts in how we develop and deploy:

1. Shift Left on AI Safety, Make it a DevOps Concern

Security and oversight can’t be final-phase checkboxes. They must be integrated into the CI/CD pipeline from day one. This means automated testing for model robustness and bias before merge, canary deployments with real-time human oversight dashboards and treating safety tests with the same priority as unit tests. The tools exist. We just have to mandate their use.

2. Build on Transparent Foundations

The antidote to fear in a complex system is observability. We must champion and contribute to open-source tools for model interpretability, audit trails and data provenance. Choose frameworks and platforms that expose their knobs and levers, not hide them. A black-box API might be easy to integrate, but it makes you a tenant in someone else’s high-risk system. Own your stack, or at least be able to see inside it.

3. Channel the Compute Towards Clear, Auditable Goals

Direct the immense energy of our community. Use internal hackathons, open datasets, and R&D budgets to tackle verifiable problems with clear success metrics, such as: “Improve the precision of this climate model” or “Reduce false positives in this diagnostic tool.” This grounds innovation in accountability and creates a portfolio of case studies that prove advanced AI can be a force for measurable good.

This path is harder. It requires more upfront design, more sophisticated tooling and a culture that views the ethicist and the engineer as co-pilots on the same sprint. But it’s the only path that leads to sovereign capability, the ability to build powerful things and know, through instrumentation and process, that they are sound. It’s the engineering discipline we’ve always prided ourselves on, applied to the most complex systems we’ve ever created.

Let’s return to that first API key. Its promise wasn’t about raw computational power. It was about agency. The power to create, to connect and to solve.

The “slow down” narrative, in its well-intentioned but clumsy execution, is a direct attack on that agency. It mistakes the tool for the threat. The real threat isn’t the engineer who wants to build—it’s the environment that makes building responsibly impossible. It’s the committee that replaces a sprint review, the fear that stops a pull request, the compliance rule that has no corresponding unit test.

Our choice isn’t between building fast and building safe. That’s a false binary sold by people who don’t ship software. Our choice is between building with disciplined speed or not building at all. And in the world of technology, the second option is a choice to be irrelevant, to cede the future to those who defined their own rules.

The next chapter of our industry won’t be written by the most cautious. It will be written by the most competent teams who figured out how to integrate the safety harness into the rocket’s design, not after it’s already on the launchpad.

Our call to action can’t be: “Slow Down.” It must be: “Build. Instrument. Prove it.” That’s how we maintain our agency, our sovereignty and our integrity in the age of AI.

Firmin Nzaji

Firmin Nzaji is an AI & Data Engineer and technical writer focused on bridging the gap between complex AI systems and their real-world, ethical application. With a background in data engineering and full-stack development, he brings hands-on experience to topics such as human-in-the-loop AI, system architecture and generative technologies—translating advanced concepts into clear, practical insights for modern teams.